whose achievements have been overshadowed

by those of his eminent father, Chaim Weizmann,

but Michael made very real contributions in both fields

which deserve to be remembered.

Chaim, who was born in Russia, is best known today

as the first President of the State of Israel,

but back when Michael was born,

the family was living in Kensington in London.

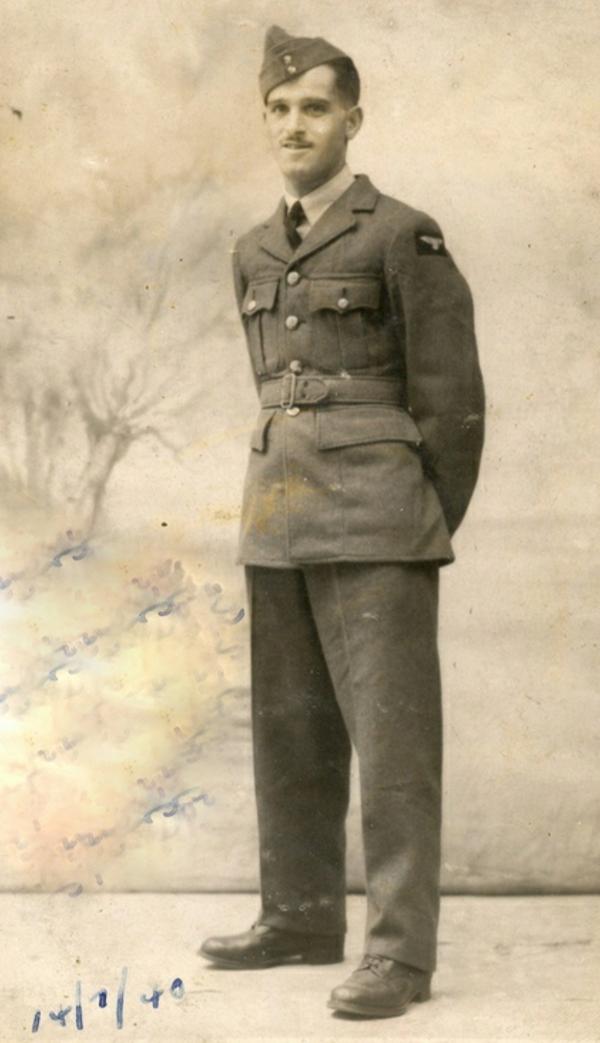

Michael attended rugby school in Cambridge University.

He was, to all appearances, a young English gentlemen.

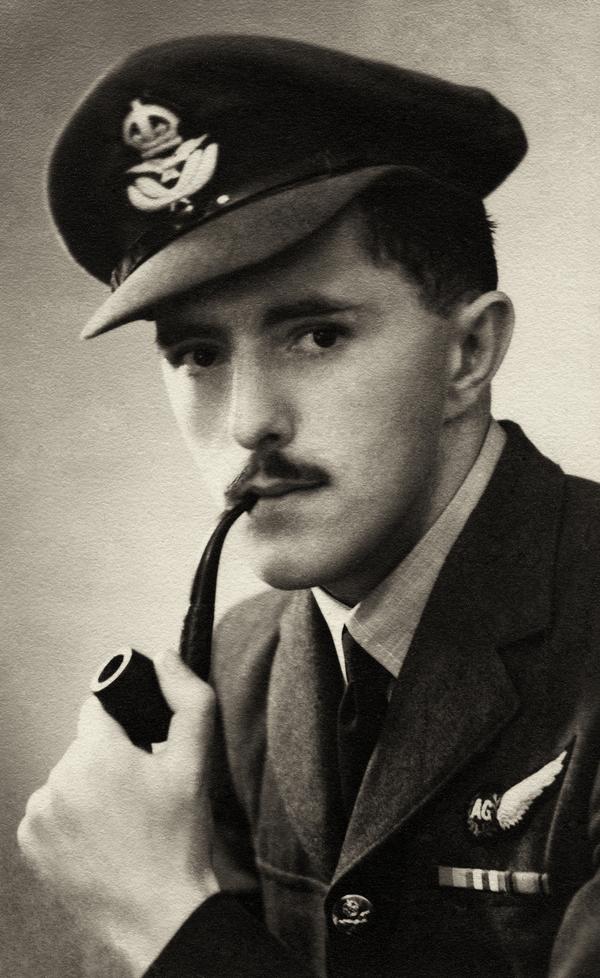

He was handsome, clever, and gregarious.

His father was proud of him, except in one detail.

Michael had no interest in Zionism.

In fact, when approached by fellow student Aubrey Solomon

with a request to join

the Cambridge University Zionist Society,

Michael declined, saying, "we have enough Zionism at home".

Michael was commissioned into the Royal Air Force

as a Pilot Officer.

He began work with the Coastal Command Development Unit

based at Kerry Sheridan in Pembrokeshire.

Now, this unit was responsible for developing

and testing all the different forms

of equipment and technology used by Coastal Command.

And this was hugely important work

because Coastal Command was responsible

within the Royal Air Force

for defending merchant shipping from attack by the enemy.

And with so much of the country's supplies coming

from abroad, those supply lines had to be kept open.

In late 1941, Michael, who was nicknamed Whizzy,

became a pilot with 502 Squadron,

a Coastal Command Squadron,

where his primary job became searching for

and attacking enemy submarines.

Equipped with twin-engine Whitley Bombers,

502 Squadron was based first at RAF Limavady

in Northern Ireland and then at RAF St. Eval in Cornwall.

It flew submarine patrols over the Irish Sea

and then over the Bay of Biscay.

So how did airplanes engage and attack submarines?

Well, the answer is it wasn't a straightforward task.

The Whitleys and their crews had problems even finding them.

Early in the war,

it was a matter of spotting the submarine visually,

either on the surface

or if its periscope happened to be visible.

But after a while,

the Whitleys were fitted with air-to-surface RADAR.

This improved the chance

of finding a submarine during the day

and made it possible at night.

But even once a submarine had been found,

it had to be successfully attacked

and this meant attacking at low level,

usually around 50 feet,

dropping a series of depth charges at equal spacings

to give the best chance of landing one close to the hull.

That was a method used on the 30th of November, 1941,

when a Whitley Bomber 502 Squadron became the first aircraft

in Coastal Command to be credited

with using air-to-surface RADAR to locate a U-Boat

and then depth charges to successfully attack it.

Now, the struggle between aircraft

and submarine was clearly a technical one.

It was a war of continuous innovation

and Michael Weizmann was leading that innovation,

first with the Coastal Command Development Unit

and then with 502 Squadron.

One of the biggest problems tackled by Coastal Command

was how to ensure safe landing back at base.

Now, this was because most patrols were flown

by individual aircraft, flying at all hours in all weathers.

Michael was well aware that 502 Squadron at Limavady

had to fly over a 1,200 foot cliff

before landing safely back at home

and this cliff had accounted

for a number of aircraft in bad weather.

Michael, working with professor Patrick Blackett,

found an answer to the problem

and that also was BABS, the blind approach beacon system.

It built on two successful systems, the German LORAN system,

which used radio beams a guide an aircraft onto its target,

and air-to-surface RADAR,

which Coastal Command was already using.

In effect, BABS allowed an aircraft

to be guided safely home by RADAR.

The navigator receives signals

from a RADAR beacon parked at the end of the runway

and the beacon gave, with perfect accuracy,

its range and glide path.

Michael was described by Frederick Dickie Richardson,

the Commander of 502 Squadron,

to be the unit's star performer.

He had developed the RAF's first

totally airborne landing aid.

He was a brilliant young man, as brilliant as his father,

but nowadays he's all but forgotten.

Flying a submarine patrol

on a stormy night over the Bay of Biscay,

Mike lost one engine and managed to send an SOS

before ditching into the sea.

Michael's body was never found

and nor were those of his five crew members.

On the 12th of February,

Michael's parents were informed that he was missing.

Throughout his life, his father Chaim never gave up hope.

In his will, he made a provision

in case Michael should return.